How to do pull-ups correctly, as Justin Moore has already brilliantly written about in several of his articles, we need the ability to protract and upwardly rotate our scapula to achieve a full overhead position with any degree of success. Too much pulling can lock us into extension and make any dreams of getting overhead on a stable thorax just that, a dream. He has made the case for balancing pulling with reaching exercises to promote movement variability and true scapular stability, which I completely agree with. However, even within a well-balanced program, we can still create excessive extensor tone if we are not careful. Pull-ups are very rarely done properly, and as a result, they can wreak havoc on an athlete’s movement variability and thus the ability to shut their system off, let alone get overhead with a barbell. The lats are heavily utilized in vertical pulling exercises like pull-ups and chin-ups due to the demands placed on them to downwardly rotate and depress the scapulae. If left unchecked, the lats can take over and dramatically pull an athlete into extension. There is nothing wrong with vertical pulling, but it cannot go un-opposed. We need to oppose the lats with the anti-extension muscles of the anterior core, serratus anterior, and low traps to maintain a well-balanced system that has the ability to shut off when needed. In addition, we need to make sure that we are performing our vertical pulling exercises in a fashion that does not promote any unnecessary extension.

First, let’s start with some functional anatomy so we are all on the same page:

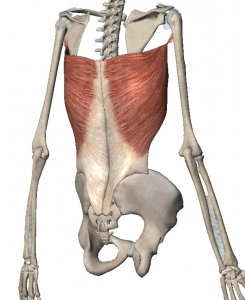

Functional Anatomy of The Lats

Attachments:

- Spinous process of the 7th to 12th thoracic vertebrae, – -Thoracolumbar fascia

- Illiac crest

- 9th to 12 ribs

- Inferior angle of the scapula

- Lesser tubercle of the humerus

- Functions:

- Internal rotation of the humerus

- Adduction of the humerus

- Extension of the humerus

- Extension of the spine

As you can see, the lats are a pretty big muscle with a very strong pull on the system due to its attachments spanning from the iliac crest all the way to the humerus. Many people know of the lats functions on the shoulder, but it must be noted that the lats are also a very powerful extensor of the spine. In fact, it could be argued that the lats are a hip flexor. Although they do not directly attach to the “hip”, they extend the spine and therefore flex or anteriorly tilt the pelvis. This can be thought of as acetabulum on femur hip flexion, which is contrasted with the femur moving in the acetabulum. So the lats as an indirect hip flexor can be indirectly wreaking havoc on your squat mobility.

In addition to the lats contributions to the movements of the shoulder, spine, and hip, they can also drastically affect how well a person can relax and recover from training. In the posterior mediastinum lies the sympathetic trunk of the autonomic nervous system. This is a bundle of nerves that send information to our brain about the status of the safety of our system in our environment. If the lats pull our thorax into extension, we will impinge on the nerves of the sympathetic trunk and be chronically in a fight or flight state. Therefore, we need the ability to resist unwanted extension to be able to shut off and recover from training or else our system will perceive that we are always training.

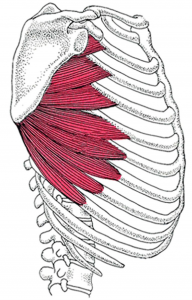

Serratus Anterior

Attachments:

- Outer surface of upper 8 ribs

- Medial angle, vertebral border and inferior angle of scapula

- Functions:

- Protracts the scapula

- Retracts the thorax under the scapula

- Externally rotates scapula

- Upwardly rotates scapula

The serratus is essentially the anti-lat. Many people know of its functions on the scapula into protraction, but perhaps the most important function of the serratus anterior is its ability to retract the thorax. Just like a femur can move in an acetabulum or an acetabulum can move on a femur, the scapula can move on the thorax or the thorax can move on a stable scapula. So when the shoulder blades move forwards, we get protraction. When the scapula stays fixed and we move the thorax backward with the serratus anterior, we get thorax or ribcage retraction. The protraction is what most people think of when they think serratus, but the retraction of the thorax component is actually much more important. Many extended individuals have actually shifted their thorax forwards, so they need the serratus anterior to act on the thorax to move the thorax backward. This gets the ribs down into internal rotation and restores the natural resting kyphosis of the ribcage. This secures the scaps on the ribcage, which gives them a nice congruent surface to fit on. As we have already written about, the scapula is round. The ribcage should be round. If we flatten out the ribcage too much, our scaps will not sit well and we will lose the leverage of the muscles that control our scapula. By restoring this natural kyphosis with the serratus, we can give our scapula a stable base to sit on so they can effectively move overhead during a pull-up or chin-up without resorting to extension at the lumbar spine.

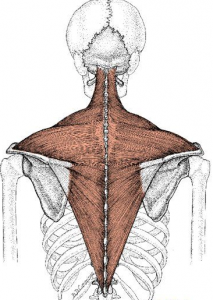

Lower Traps

Attachments:

- Spinous processes of T4-T12 vertebrae

- Spine of the scapula

Functions:

- Flexes thoracic spine from T8-T12

- External rotation of the scapula

- Depression of the scapula

- Adduction of the scapula

- Posterior tilt of the scapula

- Upward rotation of the scapula

- Ipsilateral thorax rotation (S on T)

- Contralateral spinal rotation (T on S)

Once again we realize that the muscles of the thorax and scapula have far greater roles than what most anatomy textbooks give them. Most people know the low traps depress and upwardly rotate the scapula, but few know about their other roles. I don’t want to get too far into the thorax and spinal rotation components just yet (that will be another article!), but I did want to list many of the functions to highlight how important the low traps are in thorax position and function, not just scapular movement. This is not to discount the importance of scapular movement and control, but to highlight the importance of the thorax position on everything else. When the low traps contract unilaterally in a T on S fashion (moving the thorax on a stable scapula), they cause contralateral spinal rotation by pulling the spinous processes closer to the spine of the scapula on that side. As a result of the low traps attachments on the spinous process of the lower thoracic spine, they actually pull the spinous processes up*towards the spine of the scapula when the low traps contract bilaterally. This is thoracic spinal flexion, which we have already highlighted the importance of. In many ways, the low traps function together with the serratus anterior to control S on T and T on S movement.

Resets Now that we’ve got the functional anatomy out of the way, its time to go to work. The first step in the process is getting into a position to move from. This can be accomplished with breathing drills from the Postural Restoration Institute. Here are some good options for improving the position of the pelvis and thorax while reducing tone in the lats. Note: This is not an exhaustive list of options. Any breathing drill that has previously been on Darkside will work. I just wanted to show some new possibilities.

- Lat Hang Breathing

- Wall Supported Squat w/ Reach Standing

- Serratus Squat

- Short Seated Reach

- Long Seated Pressdown

Warm Up

Now that we are repositioned, it is time to train and develop stability and control in our new positions. We now need to learn to move our arms overhead while controlling our thorax and pelvic position without resorting to extension. Here are several good options:

Supine Band PNF

- Low Trap

Half Kneeling Band PNF

- Low Trap

TRX Serratus Slides

- Serratus

KB Pullover

- Serratus/ Abdominals/ Lat Inhibition

Wall Slides

- Serratus and Low Trap

After establishing proximal stability with distal mobility, it is time to train. But we might not have the proximal stability and control to be able to tackle pull-ups and chin-ups just yet. An athlete or lifter should be able to master each of the following exercises before moving to control their body weight in a chin-up or pull-up. They can also serve as assistance exercises to keep proper scapulothoracic movement while still training pull-ups.

Regressions

Half Kneeling Single Arm Pulldown

Short Seated Alternating Pulldown

If you’ve made it this far, you’ve probably established pretty good control of the vertical pulling pattern while controlling ribcage and pelvis position in some of the regressions. Now it’s time to progress them to more difficult exercises. I like to start people with isometric chin-ups and then progress to isometric + slow eccentric variations and will often go no further with some people. I often use these variations even with people who can do full chin-ups because these variations train the low traps and anterior core much more than pull-ups do because most people will struggle with keeping a neutral position on full pull-ups. Most people will do the full movements with a very lat dominant extended strategy without abdominal opposition. This is clearly not what we want for long term thorax and scapula health and function. The iso holds and slow eccentrics force the athlete to use their abdominals to keep the ribs down, in, and back while getting the low traps to truly retract the scapula on a stable and neutral thorax instead of using the lats to drive the entire thorax into system extension

.

Reaching is important, but proper retraction and depression are important too. We need to learn to retract the scapula on a stable thorax during pulling variations if we want to maintain a well-balanced system that can easily shut off and maintain movement variability. We must first get full rib internal rotation and then must learn how to move a scapula through a FULL range of motion of retraction, depression, and downward rotation as well as protraction, elevation, and upward rotation for full function of the thorax and scapula. This requires abdominal control to keep the ribs down with serratus and low traps to move the scapula on a stable thorax. Coaching athletes to pull down aggressively and use a “big back” strategy is probably doing more harm than good. We need to first get into a more neutral position without pelvis and ribcage and then must learn how to move our scaps through a full range of motion of retraction and protraction instead of just locking them down for optimal shoulder function and health.

For more information on training review our blog on our website, or, if you’re interested in being one of our athletes, check out our page on performance training.